By Valerie Cha

“One in every 50 babies born in Japan is a hāfu—having one parent from a foreign country—amounting to 20,000 children every year” (Yoshitaka, 2018). Those who are labeled by others or identify themselves as hāfu often find it challenging to understand what it means to be a hāfu and what it means to be Japanese. According to Tamaki Denny, governor of Okinawa Prefecture, there is a fundamental problem with the term. He states, “it carries a sense of condescension and discrimination from the people using words to categorize toward those being categorized.”

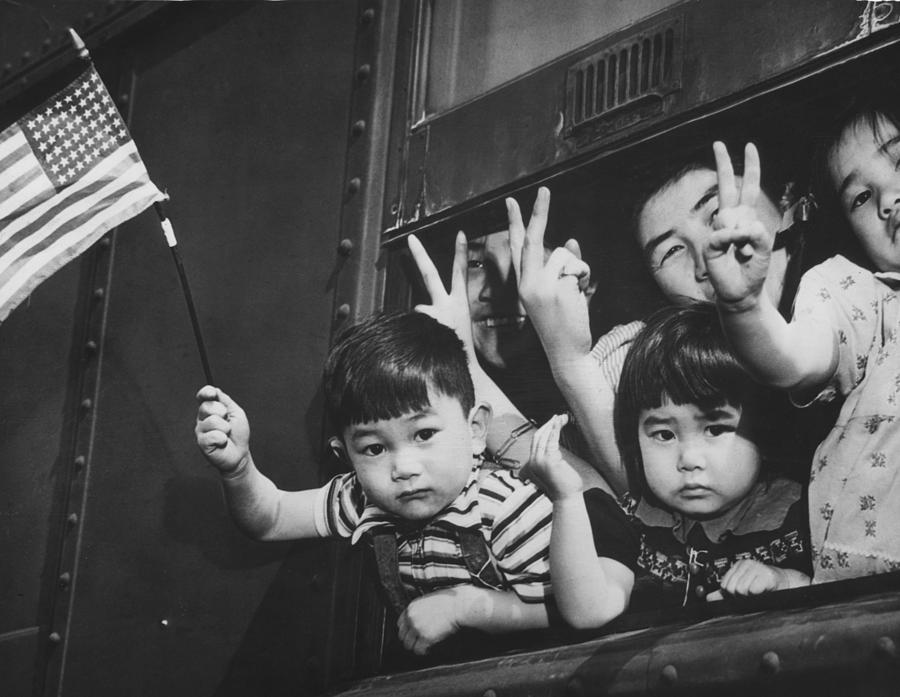

I’ve recently shed light on both American and Okinawan perspectives about the issue of American troops in Okinawa. However, what about those who are stuck in between? Citizens, who were not considered citizens by either country in the beginning, surely have their own views on the issue. For starters, the number of people living in Okinawa with mixed Japanese and American roots was a result of the Battle of Okinawa.

After a long search for the history of American Japanese, I found a scholarly article published by a modern history Ph.D. student from UC Santa Barbara, Lily Anne Yumi Welty. Welty states that immediately after the war, many of the members of the U.S. military left their children behind in the care of their Japanese mothers and the Japanese government. During my stay in Okinawa, I met a local who was a hāfu. As I asked about his story, he told me that his father was a U.S. military personnel who left him and his mother on the island. Although we did not specifically discuss the status of his citizenship, he mentioned that he has access to the American bases on the island, but he’s never actually been to the United States.

Majority of the time, both the Japanese government and American government rejected the citizenship for these multiracial children, leaving them “legally stateless”. If not all, thousands of these American Japanese children experienced intense discrimination and physical abuse due to their American features that locals symbolized Japan’s defeat (Welty, 2012). Welty mentions, “In short, they were Americans left overseas without U.S. governmental support, and often without the support of their biological parents.”

With the increase of development on the island leading to the increase in foreigner presence, the number of hāfus and number of children who are discriminated against is increasing. As they are becoming a larger portion of the population on the island, how do they feel about the presence of American troops?

Let’s examine a hāfu who has made his way to a high political leadership position, Tamaki Denny. Tamaki is the governor of Okinawa prefecture who is a son to an American Marine father and Japanese mother. Tamaki ran in the election, believing that his American heritage could help him negotiate with the U.S. government over the relocation of Futenma Air Base. He wanted the base removed from Okinawa altogether. However, as an American-Japanese, there were debates about which country, or part of himself, he was fighting to protect. “It’s not possible that the democracy of the country of my father will reject me,” Tamaki said. Although this is Tamaki’s perspective, I think it is safe to say that his thoughts resembles thoughts of other American Japanese locals as well (which is reflected in his victory). There is much confusion in terms of identity, citizenship, cultural beliefs and which side of them they should be rooting for. However, the decisions made by Tamaki and many other locals who wishes to reduce American troops, are based on ethics and made for the good of the Okinawan and American Japanese locals and the environment of the island.

This is one of my favorite posts because it’s such a unique perspective. Sure the “hafus” may not be as sure-footed in terms of ethnic identity and cultural beliefs, but the way that some choose to handle it, like Tamaki Denny, is truly admirable. Honestly, Denny’s story seems to be almost an American one, taking a mixed cultural identity and leveraging it as strength to make progress for others. Though claiming it to be prototypically American seems a bit ethnocentric. Afterall, its not like we have the monopoly on people of mixed identity. Reading your post makes me think about the story of mixed race people in other countries. How they struggle, how they think, how they triumph. You’ve given me a lot to think about.

LikeLike

Throughout most of human history, one’s identity of citizenship is the same as that of nationality. As time goes by, civilizations clash and create new identities which are not classified by the old system. These hāfus were born in such an environment with conflicted soles and strayed self-identities. I particularly liked your title, which perfectly represented the twist of fate and contradiction of culture. Given no accepted by wither group, the success of Denny Tamaki seems more inspiring and motivating. Living in the twenty-first century, we should seek consensus on culture, values, ideology, instead of still narrowly bounded by ancestry or blood. Just like Martin Luther King Jr. said in his infamous “I have a dream” speech: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

LikeLike